Has Bond sunk Solo?

I've recently finished William Boyd's attempt at a James Bond novel, Solo, and pretty thin fare it is.

It pains me to say this, as I've been a fan of Boyd's for a long time, probably since Brazzaville Beach. He picks diverse subjects to write about and his style is straightforward and without too many literary flourishes, though he's always been regarded as a posh novelist rather than a commercial one, I think.

There's a long history of writers being allowed into the Bond franchise, beginning with Kingsley Amis' Colonel Sun in the mid-sixties and carrying on through John Gardner and, latterly, Sebastian Faulks and Jeffrey Deaver. Faulks' book was good, I thought, but Deaver's effort was woeful. Boyd's attempt falls somewhere between the two.

There's a long history of writers being allowed into the Bond franchise, beginning with Kingsley Amis' Colonel Sun in the mid-sixties and carrying on through John Gardner and, latterly, Sebastian Faulks and Jeffrey Deaver. Faulks' book was good, I thought, but Deaver's effort was woeful. Boyd's attempt falls somewhere between the two.

The book separates into three sections - first, we see Bond at play in England, semi-seducing a woman but not following through; instead, we watch him as he bizarrely stalks the woman, wandering around her house while she's not there. In retrospect this seems merely a functional element of the plot to enable the third act to happen, enabling Bond to go 'solo' in the States.

The book separates into three sections - first, we see Bond at play in England, semi-seducing a woman but not following through; instead, we watch him as he bizarrely stalks the woman, wandering around her house while she's not there. In retrospect this seems merely a functional element of the plot to enable the third act to happen, enabling Bond to go 'solo' in the States.

The second and larger part of the book shows Bond on his mission, which is never really made clear either to us or to him - he's to make himself known to the leader of a rebel army in a small African country and make this soldier 'less efficient'. A critique of Britain's colonial past begins to emerge here, because the country against which the rebels are rising up is 'Zanzarim', an ally of Britain and potential supplier of untold wealth through its oil supplies. There are parallels also with the Biafran War, which Boyd observed at first hand when younger.

This part of the book begins with a hopeless exposition - a summary of Zanzarim's history and economic progress digested by Bond as a document and regurgitated to us in long paragraphs of summary. As the book progresses this summary fades into the past, out of the reader's memory, so whatever purpose it might have been intended to serve is void. We just don't need it. A few terse paragraphs from 'M' would have sufficed just as easily.

So Bond makes his way to Africa, engages in some very un-Bond-like activity (he gets lost in the jungle, spends time talking to journalists), then is betrayed when the bad folks are revealed.

Which leads us to the final section in America, where Bond goes solo to extract his revenge. The conclusion is a shoot-out, the stalest of endings, coupled with the arrival of some cavalry. The conclusion, where everything is explained, comes in a dull conversation between Bond and Felix Leiter, his old friend from the CIA. And when I say dull, I mean DULL!

To be honest, I don't know why Boyd took this assignment on. He seems to have little aptitude for writing about violence of the sort that Bond metes out or endures:

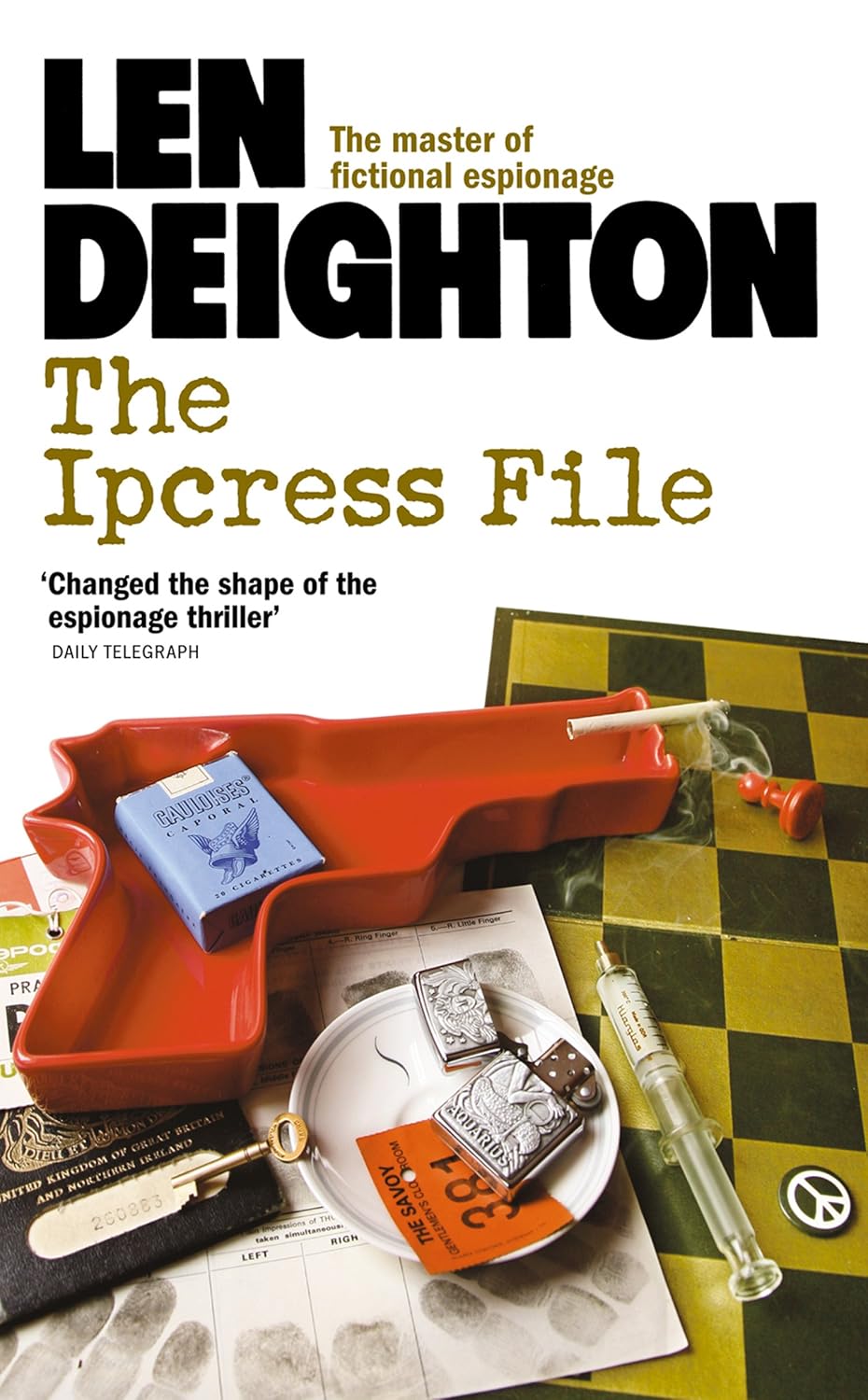

Further, the book has no driving force behind it - there is no big villain against whom Bond is pitted, no tension about whether Bond will survive or not, and no potentially world-shattering revelations. It's almost as though Boyd has been reading Len Deighton's Harry Palmer books instead of Ian Fleming's. He gives us a very close view of Bond, but unfortunately in this incarnation he's not a very interesting person. We're given some background of his experience in the war, when a youngster, but I'm uncertain how this is supposed to play into the older man we see here (Bond is 45 in 1969). This is Bond as he might be played by a sensitive Derek Jacobi, not a snarling Sean Connery.

And don't start me off about anachronisms ... I'm pretty sure no one in Government was saying in 1969, as 'M' does, 'Don't go there'. It baffles me why writers aren't more sensitive to phrases like that when writing historical pieces. Oh well, I won't go there.

I'm sure writing in the style of another author, using their characters and setting, is a tough call. But if the offer to take the Fleming Estate shilling comes in, you can always say no. On the whole, I'm beginning to think that good writers should leave the assignment well alone and leave it to the hacks, who at least have no shame and can play to the lowest common denominator. Fleming succeeded because he created a hero who was certain what he wanted to do and no qualms about doing it. These days, heroes are beset with doubts and uncertainty and flaws, and are more human because of it. Perhaps it's just not possible to write a character like James Bond any more - we're all more sophisticated than we were fifty years ago.

(Anyone noticing a similarity between the cover of Deighton's book and my own The Hard Swim gets a pat on the head.)

It pains me to say this, as I've been a fan of Boyd's for a long time, probably since Brazzaville Beach. He picks diverse subjects to write about and his style is straightforward and without too many literary flourishes, though he's always been regarded as a posh novelist rather than a commercial one, I think.

There's a long history of writers being allowed into the Bond franchise, beginning with Kingsley Amis' Colonel Sun in the mid-sixties and carrying on through John Gardner and, latterly, Sebastian Faulks and Jeffrey Deaver. Faulks' book was good, I thought, but Deaver's effort was woeful. Boyd's attempt falls somewhere between the two.

There's a long history of writers being allowed into the Bond franchise, beginning with Kingsley Amis' Colonel Sun in the mid-sixties and carrying on through John Gardner and, latterly, Sebastian Faulks and Jeffrey Deaver. Faulks' book was good, I thought, but Deaver's effort was woeful. Boyd's attempt falls somewhere between the two. The book separates into three sections - first, we see Bond at play in England, semi-seducing a woman but not following through; instead, we watch him as he bizarrely stalks the woman, wandering around her house while she's not there. In retrospect this seems merely a functional element of the plot to enable the third act to happen, enabling Bond to go 'solo' in the States.

The book separates into three sections - first, we see Bond at play in England, semi-seducing a woman but not following through; instead, we watch him as he bizarrely stalks the woman, wandering around her house while she's not there. In retrospect this seems merely a functional element of the plot to enable the third act to happen, enabling Bond to go 'solo' in the States.The second and larger part of the book shows Bond on his mission, which is never really made clear either to us or to him - he's to make himself known to the leader of a rebel army in a small African country and make this soldier 'less efficient'. A critique of Britain's colonial past begins to emerge here, because the country against which the rebels are rising up is 'Zanzarim', an ally of Britain and potential supplier of untold wealth through its oil supplies. There are parallels also with the Biafran War, which Boyd observed at first hand when younger.

This part of the book begins with a hopeless exposition - a summary of Zanzarim's history and economic progress digested by Bond as a document and regurgitated to us in long paragraphs of summary. As the book progresses this summary fades into the past, out of the reader's memory, so whatever purpose it might have been intended to serve is void. We just don't need it. A few terse paragraphs from 'M' would have sufficed just as easily.

So Bond makes his way to Africa, engages in some very un-Bond-like activity (he gets lost in the jungle, spends time talking to journalists), then is betrayed when the bad folks are revealed.

Which leads us to the final section in America, where Bond goes solo to extract his revenge. The conclusion is a shoot-out, the stalest of endings, coupled with the arrival of some cavalry. The conclusion, where everything is explained, comes in a dull conversation between Bond and Felix Leiter, his old friend from the CIA. And when I say dull, I mean DULL!

To be honest, I don't know why Boyd took this assignment on. He seems to have little aptitude for writing about violence of the sort that Bond metes out or endures:

The first shot hit [the man] just in front of his left ear sending a fine skein of blood spraying from his head and the second smashed into his chest, slamming him heavily against the wall. He slid down it, leaving a thin smeary trail of blood and toppled over. Adeka screamed and gibbered, huddling in the corner.Here, the screaming Adeka comes too late after the action that provoked the scream - surely he would have screamed when the shot was fired, not after the man slid down the wall to the floor. Similarly, Agent Massinette 'irrupting' into the room seems to come a long time after he fired the bullet - was he outside when he fired it? How did he do that? What's more, the use of the word 'irrupted' pulls the reader up short as s/he tries to place its meaning. It's a good word, but it's too dramatic and too obscure to use at this point in a moment of dramatic tension.

Agent Massinette irrupted into the room, gun levelled at Adeka. He was followed immediately by Brig Leiter. Bond heard the clatter of other footsteps coming down the corridor overhead.

Further, the book has no driving force behind it - there is no big villain against whom Bond is pitted, no tension about whether Bond will survive or not, and no potentially world-shattering revelations. It's almost as though Boyd has been reading Len Deighton's Harry Palmer books instead of Ian Fleming's. He gives us a very close view of Bond, but unfortunately in this incarnation he's not a very interesting person. We're given some background of his experience in the war, when a youngster, but I'm uncertain how this is supposed to play into the older man we see here (Bond is 45 in 1969). This is Bond as he might be played by a sensitive Derek Jacobi, not a snarling Sean Connery.

And don't start me off about anachronisms ... I'm pretty sure no one in Government was saying in 1969, as 'M' does, 'Don't go there'. It baffles me why writers aren't more sensitive to phrases like that when writing historical pieces. Oh well, I won't go there.

I'm sure writing in the style of another author, using their characters and setting, is a tough call. But if the offer to take the Fleming Estate shilling comes in, you can always say no. On the whole, I'm beginning to think that good writers should leave the assignment well alone and leave it to the hacks, who at least have no shame and can play to the lowest common denominator. Fleming succeeded because he created a hero who was certain what he wanted to do and no qualms about doing it. These days, heroes are beset with doubts and uncertainty and flaws, and are more human because of it. Perhaps it's just not possible to write a character like James Bond any more - we're all more sophisticated than we were fifty years ago.

(Anyone noticing a similarity between the cover of Deighton's book and my own The Hard Swim gets a pat on the head.)

Keith, at the risk of sounding overly cynical, writing a Bond novel seems like a thankless job to me so the only reason to take it on is the guaranteed payday. Maybe that was Boyd's goal here. Trying to figure out how to make money off my own writing, I can't begrudge an author for doing that but I can avoid reading such books. I don't plan on reading any updates of Sherlock Holmes, Philip Marlowe or the reported ones of Hercule Poirot either. It seems to me Charles Schulz had the right idea when he retired Peanuts (not knowing he would die the day the last strip was published): he refused to grant any other cartoonists the right to carry on his strip. Maybe that's a little different than a book series but I think the idea is a good one for novelists as well. I don't want to see anyone "carrying on" Elmore Leonard or John le Carre either.

ReplyDelete